POSTED 06.11.22 / BY C YATES

design FOR BEHAVIOR CHANGE

CATEGORIES

Design

Future

Connected

Methodology

Innovation

Technology

ABOUT ME

I am passionate about innovative design and creating user experiences at the intersection of art, science and technology.

RELATED POSTS

Design Methods

Cultivating Micro-Moments

The world is changing, and not for the better, the evidence is indisputable that humanity has played a part in this change, but is also pivotal in preventing the change from becoming unstoppable, and reversing some of the effects. However to achieve this humanity itself must change, and this is where design can play a key role.

"Human behavior flows from three main sources: desire, emotion, and knowledge." -Plato

There are many ways that humanity and behaviour needs to change; become a more tolerant society, engage in diplomacy rather than aggression, reduce carbon emissions, use more renewable energy, assimilate the circular economy, use metrics other than short-term growth as success markers, make decisions based on sustainability, and embrace the shared economy. Design can help influence much of this change, non more so than in making better decisions, and embracing new ways of doing things. This is evident in different areas of life from energy consumption (switching to renewable sources), e-commerce (ethical purchasing), health and well-being (shift to a more plant based diet and the importance of regular exercise), and mobility (access over ownership).

Promoting the principles of circular economy and the new business models advocated by the circular economy can represent a solution for a more prosperous society, less dependent on primary and energy resources and more environmentally friendly. The sharing economy, which primarily involves the transformation of traditional market behaviours into collaborative consumption models, that ensure a more efficient and sustainable use of resources, is part of the circular economy and has generated business models that are compatible with it. The basics of the sharing economy have always existed, as owners of under-utilised assets such as a car, a power tool, or an empty guest room searched for those who desired the temporary use of such assets in their community via bulletin boards or newsletters. What has changed is the emergence of mobile software platforms that allow these two parties to easily come together whenever and wherever they wish. This significant reduction in searching and transactional frictions, as well as the flexibility to conduct a trade anytime and anywhere from a smartphone, has driven the sharing economy into the daily lives of many people, changing patterns of consumer behaviour.

According to a 2020 study from Lund University on car sharing services (CSS) in Stockholm one can observe that CSS has the potential to reduce car ownership and resultant car mileage, emissions, congestion and the need for parking space. It can also increase preferences towards fuel-efficient or electric cars and complement public transportation and active mobility. On the other hand, the available information also suggests that certain car owners cannot forego car ownership so to begin with CSS may only substitute the services of a second/third car and require more behaviour change action to fully engage all car owners. The study also reveals various factors motivating but also hindering the (potential) adoption of CSS. On the positive side, economic reasons, convenience, environmental concerns, conformity towards emerging social norms, and innovative business platforms are indicated to foster the (future) adoption of CSS. On the contrary, the perceived low cost of owning a car, reliability, security and aspects preventing accessibility (e.g. parking) are often cited as factors limiting consumer uptake. The study concluded on the need to further understand the motivations, behavioural aspects and environmental impacts affecting the adoption of CSS including a better understanding of the behaviour change and cognitive biases that may be applicable to CSS.

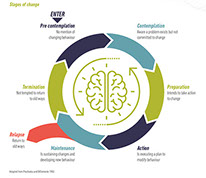

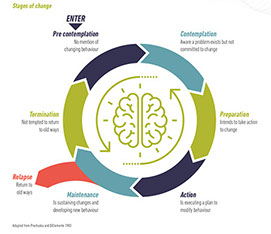

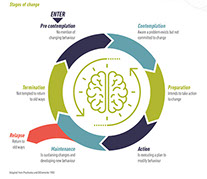

How might we describe the process of behaviour change? Healthcare has mostly adopted the Transtheoretical model (TTM) which follows five stages of behaviour change; pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Another example derived from social change, the COM-B model, cites capability (C), opportunity (O), and motivation (M) as the three key factors capable of changing behaviour (B). Capability refers to an individual’s psychological and physical ability to participate in an activity. Opportunity refers to external factors that make a behaviour possible. Lastly, motivation refers to the conscious and unconscious cognitive processes that direct and inspire behaviour. However you may look at it behaviour change it is not easy and relies on completing a number of interdependent factors or steps, any of which can be a stumbling block to effective change. When we talk of behaviour change in the sense of impacting humanity we are looking to effect permanent change such that the effects alter our habits and behaviours for the long term. As much as the world needs humanity to be more sustainable, humanity needs sustainable behaviour change in order to make a difference.

Today there exists many models, methodologies, principles and techniques on how to approach the problem of behaviour change. However many of these relay on the same fundamental building blocks in understanding what needs to change, seeking the means or resources to effect change, having the willpower and motivation to take action, and knowing the resulting outcome of change.

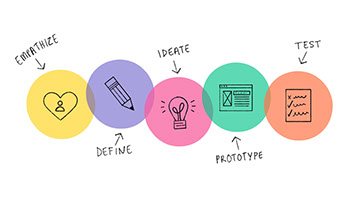

For many designers, and non-designers alike, Design Thinking has been a popular and useful methodology to help solve problems. Design Thinking is a non-linear, iterative process that teams use to understand users, challenge assumptions, redefine problems and create innovative solutions to prototype and test; Involving five phases—Empathise, Define, Ideate, Prototype and Test, it is often most useful to tackle problems that are ill-defined or unknown. A similar, if not more simple philosophy, is often associated with product design, that of Discover (think) - Define (make) - Develop (create).

Design thinking and other methodologies are great constructs to bring about new ideas, concepts, or ways of thinking, but as constructs they remain separate from reality, it is with product design that we can seek to cross that boundary and effect real behaviour change. Looking at the tenants of behaviour change, the approach to problem solving of design thinking, and the philosophies of product design, it seems plausible to combine these in a way that allows for a more effective implementation of behaviour change with product design.

The first stage in design thinking is Empathise; gain an empathetic understanding of the problem you’re trying to solve, typically through user research and introspective thinking. Equally the first step in TTM is pre-contemplation, and in Social Cognitive theory is Self-efficacy or a judgment of one’s ability to perform the behaviour, and in COM-B there is Capability which includes the knowledge/ psychological strength, skills or stamina. These are all forms of understanding and introspective thinking and the examination of one's own conscious thoughts and feelings.

"Learning to stand in somebody else's shoes, to see through their eyes, that's how peace begins. And it's up to you to make that happen. Empathy is a quality of character that can change the world." - Barack Obama

Discover - understanding

To design for behaviour change we should layer understanding the mind as part of Discovery to gain a better insight on how we make decisions and how our cognitive mechanisms can support (or hinder) behaviour change. Marketeers having been using an increasing level of awareness in how the mind works for many years in the pursuit to sell more. From product placement in supermarkets (those placed at eye level sell more) to the smell of fresh baked bread to attract customers into a shop.

They are exploiting the fact we have two modes of thinking in the brain—one is deliberative and the other is intuitive. Psychologists have a well-developed understanding of how they work, called dual process theory. Our intuitive mode (or “emotional” mode; it’s also referred to as “System 1”), is blazingly fast and automatic, but we’re generally not conscious of its inner workings. It uses our past experiences and a set of simple rules of thumb to almost immediately give us an intuitive evaluation of a situation like a “gut feeling”. It’s generally quite effective in familiar situations, where our past experiences are relevant, but does less well in unfamiliar situations.

Our deliberative mode (aka our “conscious” mode or “System 2”) is slow, focused, self-aware and what most of us consider “thinking.” We can rationally analyse our way through unfamiliar simulations, and handle complex problems with System 2. Unfortunately, System 2 is woefully limited in how much information it can handle at a time (we struggle holding more than seven numbers in short-term memory at once), and thus rely on System 1 for much of the real work of thinking. These two systems can work independently of each other, in parallel, and can disagree with one another—like when we’re troubled by the sense that, despite our careful thinking, “something is just wrong” with a decision we’ve taken. Just like the first time that users try out a product, they immediately judge it based on their prior experiences and associations. You don’t have time to convince them logically; the judgment is made in an instant. Instead, you must proactively gain insight into their prior associations to avoid land mines and find positive hooks that help people change their own behaviour. This is where existing discovery activities such user research play a part.

In the mobility space the rise in city usage of e-scooters and e-bikes has been in part to the attention paid to the design of the first time use. Download and quick registration of the companion app along with GPS allows the user to quickly locate a suitable scooter. Use of QR code and camera scanning completes the transaction making the first time experience simple and effective.

When the System 1 is in control we often refer to this as a habit. A habit is a repeated behaviour that’s triggered by cues in our environment. Its automatic—the action occurs outside of conscious control, and we may not even be aware of it happening. Habits save our minds work; we effectively outsource control over our behaviour to cues in the environment.

Most of our daily behaviour is governed by our habits or intuitive mode. We’re acting on learned patterns of behaviour based on our past experiences, or on simple rules of thumb (cognitive shortcuts or heuristics built into our mental machinery). Research estimate that roughly half of our daily lives are spent executing habits and other intuitive behaviours, and not consciously thinking about what we’re doing. Our conscious minds usually only become engaged when we’re in a novel situation, or when we intentionally direct our attention to a task.

We’re hardwired to build habits—they save our minds work. It’s difficult to overcome existing habits, but we can intentionally create new habits or change existing ones. Once formed, they are resilient. To build them requires identifying a specific, unambiguous cue, a stable routine, and, ideally, a reward that occurs immediately after the person takes action.

In the area of car sharing services (CSS) opportunity exists to tap into a users stable routine, such as the daily commute or big shopping trip, to present car share as a viable alternative. Once a user makes the decision they should be rewarded for positive behaviour change.

Another aspect of understanding is why people take certain actions and not others? From moment to moment, why do we undertake one action and not another? There are five preconditions for action that must occur, at the same time, before someone will act. Behaviour change products encourage action by influencing one or more of these preconditions: cue, reaction, evaluation, ability, and timing. These five mental processes—detecting a cue, reacting to it, evaluating it, checking for ability, and deciding on the right timing—are the preconditions to action and form the action funnel.

Our minds can’t handle large amounts of information, and they protect us from being overloaded by using a set of mental filters. For example, in-attentional blindness means we simply don’t see things we aren’t looking for when we’re concentrating heavily. This is strikingly observed in Chabris and Simons’s famous study in 2009 where half of the people watching a basketball game failed to see a person in a gorilla outfit walking across the screen!

An action arises as a result of two factors; external cues - something in our environment can trigger us (like an email or text message) to think about it, and internal cues -our minds can drift into thinking about the action on its own, through some unknown web of associated ideas (which may themselves have been cued externally).

When users are just starting to undertake a new action, external cues are vital.

To get people to change behaviour and consider access over ownership for mobility, the product will need to be in locations that users encounter on a daily basis. Consider using different cues from billboard adverts, mobile notifications, to social media posts. Also seek to build strong associations with parts of the users existing routines.

The decision of when to take action, its timing, can be driven both by a sense of clear and present urgency, and by other, less forceful but still important factors. Urgency can come from a variety of sources. External urgency, Internal urgency, Specificity, Consistency, The decision to act at a particular time also arises, in part, from our motivation (emotional and deliberative) to take the action. You can think about the timing of action in terms of two factors: what the product actively does to make the timing ripe for action, and what it does to align with the times when a person is naturally inclined to take action.

Instead of making something urgent, products can wisely align themselves with events in a user’s life that already provide that urgency. The user may need to take a similar action as part of their work and the product can hook into and build on that opportunity. This is similar to the ancient Greek concept of “kairos” or the opportune time—it’s the product’s job to be there when the opportune time for action arises.

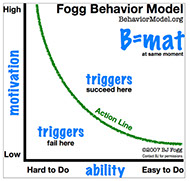

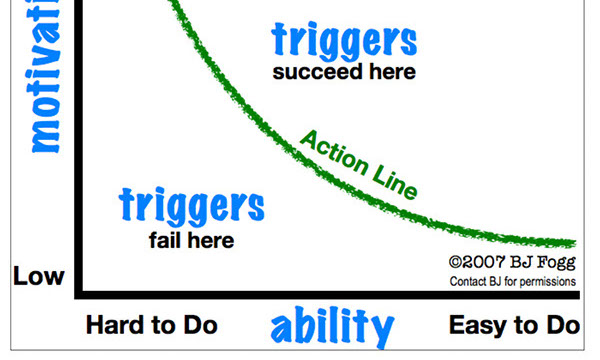

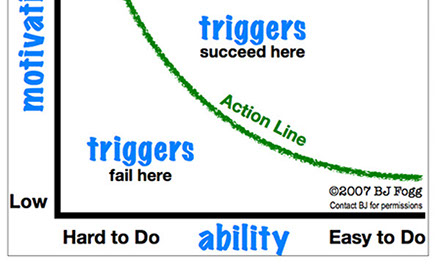

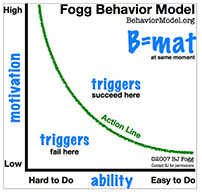

In relation to CSS urgency can be a decisive factor in decision making, fulfilling an immediate need such as an unplanned trip, the need to move large items, a change in plans etc. as long as CSS can be seen as a viable option, is easy to use, and fits the value that the user ascribes to the product and action. An important thing to remember about the preconditions for action is that at each stage, the user only continues on if the action is more effective or better than the alternatives. There are always alternatives, including other cues that seek to grab attention (like Uber discount emails), other actions we are intuitively and consciously assessing (what it would cost to run a car versus paying for access), or other priorities that could be urgent (visiting friends and family rather than going on that trip). From a product design perspective, that means you should consider not only how well the product guides the user through these stages, but what else is competing for the users scarce time and mental resources. Removing distractions is a key part of structuring the individual’s environment. Other aspects to consider are motivation and how easy the action is to do. This is one of the many ideas that BJ Fogg (2007) built into his Behaviour Model in that making the action easier or making the user more motivated won’t buy you as much as you might think. His model has three factors; motivation, ability, and trigger. Motivation is defined as pleasure/pain, hope/fear, acceptance/rejection (which has elements of an emotional reaction and a conscious evaluation), and ability roughly corresponds to the lack of resources. The trigger of his model corresponds to the “cue” and Fogg argues that in order for an intentional action to occur, you need all three elements. You can encourage an action by increasing a person’s ability to act (decreasing costs) or increasing motivation. In each case, the boost it provides to the person decreases as the action becomes easier and more motivating, when the action is very difficult, a bit of help to make it easier is very powerful. When the action is already easy, making it even easier isn’t going to change behaviour as much. In economic terms, this is known as the law of diminishing returns.

“Do the difficult things while they are easy and do the great things while they are small. A journey of a thousand miles must begin with a single step.” - Lao Tzu

Define - strategies for behaviour change

The next stage in design thinking is to use the data collected to define the core problems identified up to this point in a human-centred manner. The Define stage helps the team collect great insight to establish features, functions and other elements to essentially set the strategy to solve the problem. When considering the stages of behaviour change TTM defines the next step as contemplation, whilst COM-B moves towards defining the opportunity or the external factors which make the execution of a particular behaviour possible, and Social Cognitive theory looks at Outcome Expectations - a judgment of the likely consequences a behaviour will produce. These are are all forms of strategic thinking, and in product design for behaviour change this should form part of the Define phase.

While you can make an action rewarding, easy, familiar, socially acceptable, or any number of the other things, the activity still involves work for the user. Ideally, if the product could offer to shift the user’s burden in identifying clever ways to make active participation by the user unnecessary beyond giving informed consent. This is the eliminating work strategy and is evident when products use defaults; good cameras have a simple solution that help people take quality pictures, but still provide users power options: the cameras have default settings that are simple to use and would provide a quality picture in most scenarios, eliminating the work for the user. Another way to eliminate the work is make it incidental; have the action come along for the ride with something else that users are going to do anyway. In other words, don’t have them think about doing the action at all. Make the action happen automatically when the user does something else. A classic example is getting people to take more vitamins just by adding them to food people already consume. Or the Apple Watch that automatically registers a users exercise such as walk or run without any user interaction. For CSS the option may exist to provide access to the car just as a part of booking a hotel or trip, or offered by the supermarket as part of the weekly shop, or arranged by a company for the regular commute of employees.

Another strategy is to help the user form new habits. Before a habit is formed the user still needs to choose to act. With habits, the problem is to help the person “get into the mindset”—to start taking the action, so that the mind can make it habitual. Habits can be created out of simple repetition (cue-routine-repeat), or have the added feature of a reward (cue-routine-reward) that drives the person to repeat the behaviour. Users can form habits by simple repetition, but then the burden of work and will-power is all on the users side. When designing for behaviour change, it is more effective to add a reward at the end to help bring people back to the action while the habit is forming. For CSS to help users build action into a habit a reward should be part of the experience. This could take different forms such as discount off the next access, or accumulate reward points (airlines used air-miles very successfully for many years at the growth of the industry - in hind site this was not the behaviour that should have been rewarded) which can then be redeemed for a free car access. The reward need not be offered every time, as long as it is still clearly tied to the routine. Random rewards are quite powerful in some circumstances. In the operant conditioning literature, habits with random reinforcement take the longest to form but also take the longest time to extinguish once the reward is no longer given.

The previous two strategies involved removing user work and simplifying the problem. But the simplified problem still requires a conscious choice to act. The conscious mind must be engaged at some point. Ideally, that interaction entails informed consent—and the product automates or defaults the rest. Or the conscious choice can be to start down the path of habit formation or habit change. Whilst this requires additional effort on the part of the user, a head-on approach can help educate the user to think about the action, and take the necessary steps (consciously) to make it happen. For CSS this could mean providing education material on the benefits, not just for the individual, but also for the local environment and society in general.

“All men can see these tactics whereby I conquer, but what none can see is the strategy out of which victory is evolved.” - Sun Tzu

GALLERY

Mobility and car sharing are proponents of behaviour change

Car sharing services CSS are looking to change face of cities and urban life

TTM stages of behavioural change

Stages of Design Thinking

The importance of supermarket product placement on intuitive selection

micro mobility adoption is driven by the first time experience

Action Funnel

BJ Fogg behaviour model

Apple watch auto detects when you exercise

Consider who is the target actor and create behaviour persona

CSS can mean reclaiming the streets as social spaces

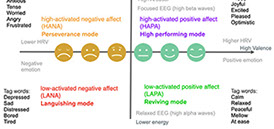

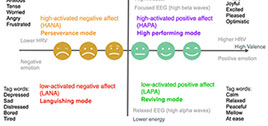

Use biometrics as part of user testing to measure unconscious System 1 behaviour change

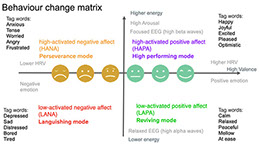

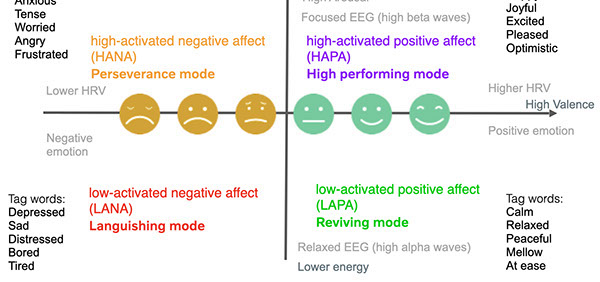

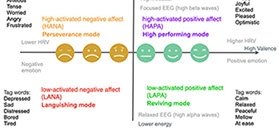

Behaviour change model of affect

This is the challenge

14 - 14

<

>

Define - what to accomplish

The next stage in the TTM behaviour change model is preparation and in the product design process preparation is to clarify the target outcome; what is the product supposed to accomplish? What will be different about the real world when the product is successful? The target actor; who do we envision using the product? Who will do something differently in their lives, and thus accomplish the target outcome? The target action; how will the actor do it? What behaviour will the person actually undertake?

Define the real-world measurable outcomes that the product should have and that define the success or failure of the product. Translate company-specific goals into real- world outcomes that the user actually cares about. Brainstorm actions that people might make the product’s intended outcome a reality. Trim each action down to its Minimum Viable Action.

Following regular design thinking methodology definition should also cover user research and document the characteristics of the user. For behaviour change we also consider prior experience with the action, prior experience with the product, existing motivations to act, their relationship with the company (trust), and barriers to action. The research enables behavioural personas to be generated—groups of users that you expect will respond differently to your product’s attempts to change behaviour. Rate the potential action for users to take in terms of their effectiveness, cost, motivation, and feasibility for the user. Select the ideal target action, based on these criteria.

In the COM-B model the third component for behaviour change is motivation. As we learned from BJ Fogg’s work on habit formation, you can encourage an action by increasing motivation. In each case, the boost it provides to the person decreases as the action becomes easier and more motivating. When considering the target outcome it is important to include how to effect motivation by looking at the internal processes which influence the users decision making and behaviours. There are two main components to this: Reflective Motivation: reflective processes, such as making plans and evaluating things that have already happened, and Automatic Motivation: automatic processes, such as our desires, impulses and inhibitions. Using the example of physical exercise with regards to motivation, an individual’s lack of capability and opportunity may result in their ‘need’ to be physically active being overshadowed by their ‘want’ to relax and remain inactive; being inactive is likely to be a behaviour that they have high capability and opportunity for. However, if the above changes are made to the individual’s perceptions of capability and opportunity, then their motivation to carry out the behaviour may be increased.

Based on this assumption, the key to behaviour change would be to establish physical activity as something the individual not only ‘needs’ but also ‘wants’ to do. This can be done by encouraging the individual to consider the long-term benefits of physical exercise (reflective motivation) and use these benefits to make physical activity seem the more desirable option as opposed to inactivity (automatic motivation). Framing physical activity as something they both need and want could motivate them to execute the behaviour, and override the competing behaviour of remaining inactive. This idea can also be applied to CSS where the user has a ‘need’ to use more sustainable alternatives but their ‘want’ to keep owning their car has higher perceived capability (it requires little effort to use a car they already own) and opportunity (the perceived cost of owning a car versus the access alternative). Making the user more aware of the wider benefits of CSS such as less traffic on the roads leads to reduction in accidents and deaths, conversion of parking areas into more social spaces, less CO2 emissions with electric vehicle CSS, and a better understanding of the cost pariy between CSS and car ownership, then their motivation to switch from car ownership to access may be increased.

Include as part of the defined outcomes how users are motivated to act, and that motivation is part of the experience. Either accent their own existing motivation, or motivate them with reward, approval, social status, or other extrinsic factors. Ensure they are cued to act, and ensure they know they are succeeding or failing—give them

actionable feedback. Avoid other behaviours that are competing for their attention, ideally piggyback onto something they are already doing. The culmination of the discovery, definition strategy, and outcomes lead to a behavioural plan for the action you want users to take to effect the desired behavioural change.

“If you don't like something, change it. If you can't change it, change your attitude.” - Maya Angelou

Define - experimentation

Following the TTM behaviour change model the next step is the action that the discovery has been looking to shape and definition has formulated a strategy to execute. However in design thinking terms this is just a hypothesis that should be tested, validated, and refined before considered as complete. This is where the design process of ideating around the user flow, interaction, and interface, leading to rapid prototyping of the best potential concept to enable the user action by considering the capability (pre-contemplation), opportunity (contemplation), and motivation (preparation).

A way to do this is by chopping up the behavioural plan into the raw material for designing the product. In an agile world, that’s user stories. In a sequential development world, that’s an outline for the full product requirements. Initially, try to avoid specifying the interface design based on the behavioural plan. Focus on what the product needs to do, and come up with a compelling experience for the product. You can employ design patterns for behaviour change that are familiar to users, such as trackers, rewards, or reminders. Prior to testing the concept review the designs for the five action funnel prerequisites: cue, reaction, evaluation, ability, and timing. Apply specific tactics in each of these areas, leveraging insight from behavioural science.

When testing the concept prototype look at people’s behaviour as well as the conscious, verbal feedback. People often say one thing but mean another. For example in getting people to do more exercise they may express excitement and interest in being presented with a screen that lets them customise every aspect of their exercise plan, but be completely confused when trying to use it in practise.

Other cognitive quirks also muddy the conscious verbal feedback that participants give. For example, we have a strong tendency to generate meaningful narratives for our past behaviour even when luck and circumstance directed our actions. As well as listening to what people say, look for what they do—for example do they spend a lot of time trying to make a decision, do they actually complete a sequence, or do they give up early?

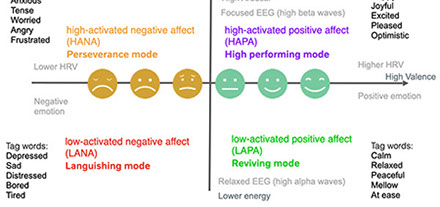

In testing designs for behaviour change it is effective to measure the users emotions and physiology along with the ‘think aloud’ verbal responses and actions they do. By using sensors from biometric tracking devices such as Smartwatch, chest strap, dry-electrode headsets. A real-time data stream of the users physiological biomarkers including heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV), breathing rate, skin temperature & electrodermal activity (EDA), facial electromyography EMG (basic emotions), and EEG brain activity (attention and valance) can be captured and overlayed in a time recording of the user testing session.

With this information an understanding of the relationship between the biometric levels for EEG, EDA, EMG, and the understood psychophysiological or emotional state can be analysed along with the verbal and observational data to validate if the action is having a behavioural change effect at both the users conscious and unconscious level. With reference to my previous research for the London Fusion project I presented a mapping of biometric states for EDA/GSR (arousal); there is a well proven relationship between sympathetic activity and emotional arousal, although one cannot identify the specific emotion being elicited. Fear, anger, startle response, orienting response and sexual feelings are all among the emotions which may produce similar EDA responses, however an increase/decrease in EDA level can be associated with user excitement / boredom emotions. EMG (valance); there is a clear understanding of the relationship with the facial muscle responses and the emotional valance levels ranging from unpleasant (frustrated) to pleasant (optimistic). EEG (attention); is the most difficult area to map, however there are understood relationships between various brainwave activity and human mental states and conditions. In addition combinations of brainwave activity can be related to cognitive load shown with attention and meditation levels.

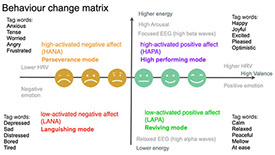

In recent years I have expanded the model in exploring different relationships and applying it to a continuous monitoring of a users state of mental well-being by understanding the physiological patterns related to negative and positive emotions in relation to measures of arousal and valance. With this I created a model encompassing The Circumplex Model of Affect and emotion tag word triggers for well-being, where biometric data and the arousal / valance relationships could be related to states of high-activated positive affect (HAPA) High Performing mode, high-activated negative affect (HANA) perseverance mode, low-activated positive affect (LAPA) reviving mode, and low-activated negative affect (LANA) Languishing mode. This can be applied to understanding behaviour change and the degree to which the product design action elicits the high performing mode HAPA, indicating a high probability of behaviour change, or the perseverance mode HANA where a low probability of behaviour change is exhibited, and to also identify when user exhibits reviving mode LAPA indicating a desire but the design is lacking enough optimism or excitement, and if users show signs of languishing mode LANA indicating they may have deep routed beliefs against the action that would require a different approach, and could be considered as not the target audience for the designed action.

Develop - measuring impact

With the action definition tested, validated and the design refined to reflect the results, the work can begin on creating the design components, elements, assets, and guidelines to implement the action and effect behaviour change. To understand if the implementation is having the desired effect requires establishing metrics for success. This can often be done by building analytics into the product to measure key data points affecting the action. In addition this can be added to real-world data collected on the outcomes of the action. In such cases, where it is not possible to regularly gather real-world data, there are other ways to benchmarking the product’s impact: Use a proxy and benchmark the impact the product has on this intermediate or proxy user behaviour that you can measure regularly. Determine how to accurately measure the real-world outcome at least once. Build a bridge between the intermediate user behaviour you measure regularly and the real-world outcome you care about.

In addition to measuring success factors it is also important to adopt a continuous discovery methodology by observing how real users are actually using the product, to see where they struggle, and especially what obstacles they face on the path to behaviour change. Examine the application’s data, and find out where users are falling off for each step of the process that leads up to the target action. Avoid obstacles by simply removing the problematic functionality, where possible. Otherwise, use the ‘Action Funnel’ to diagnose what’s happening at a particular obstacle. Use small, quick tests to evaluate potential solutions before making significant design iterations.

Ideally, the outcome of any product development process, especially one that aims to change behaviour, is that the product is doing its job and successfully automates the behaviour, builds a habit, or reliably helps the user make the conscious choice to act. Designing for behaviour change is about final, objective outcomes, and what’s really in the best interest of the users, of society, and of humanity as a whole.

“Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we've been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.” - Barack Obama

LEAVE A COMMENT